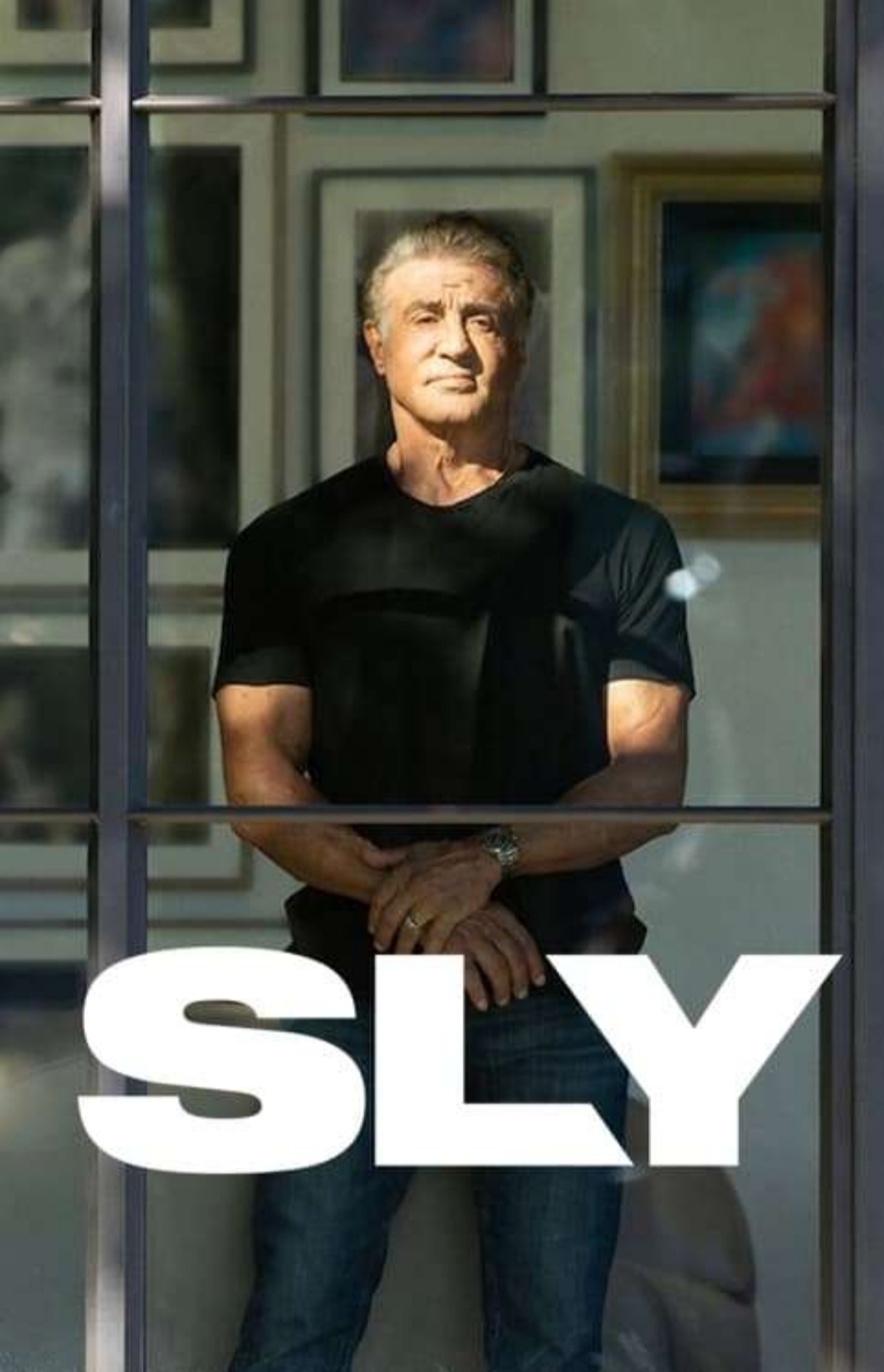

Sly Film Analysis 2023

Sly Film Analysis While Sylvester Stallone was initially recognized for his physique, the documentary “Sly” by Thom Zimny proves that it was really the actor’s voice that propelled him to fame. The film makes it evident that there are really two competing narratives. Stallone’s slurred, New York-accented bass croak is one example; he had facial paralysis during birth, which affected his ability to speak clearly. The screenplays that Stallone creates (and often rewrites, sometimes on the fly) provide the other voice.

The only major literary honor Stallone has been nominated for is the Oscar for the best screenplay of all time for the movie “Rocky,” which appears to be as much as an incentive for Stallone’s personal Hollywood Cinderella narrative as it is for the script itself. But as “Sly” shows, whatever Sylvester Stallone works on automatically becomes into a Stallone movie, even if that wasn’t the original plan. Whether he’s playing a human-sized character like Rocky Balboa or gentle deputy sheriff Freddy Heflin in “Copland,” and a jacked-up killer like John Rambo or the snarling heroes of “Cobra,” “Demolition Man,” or “Judge Dredd,” the words, stories, and themes all come from a personal place.

Both Stallone’s influence and the influence of junior artists who grew along viewing his movies ensure that anything he touches sounds like him. There was no way to mistake his art for someone else’s, for better or for worse. He continued trying new things, mixing red meat action pictures with efforts at humor (“Oscar,” “Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot”) and romantic (“Rhinestone”), all within a remarkable fourteen-year run that included the first five “Rocky” movies and three “Rambo” features.

Even Arnold Schwarzenegger, his only realistic competitor for the he-man cinema crown in the 1980s and ’90s, admits to “Sly” saying he was in marvel of Stallone’s ability to stay one step beyond him even at the height of his desire and fortune, and having enough focus or drive to concurrently wear four hats (actor, writer, director, producer) on that it has the signature assignments.

“Sly” delivers Stallone his rightful place as a pop cultural powerhouse and then some. Zimny is well-known for his work on Bruce Springsteen documentaries and music videos. Stallone’s upbringing in Hell’s Kitchen, New York City, and his turbulent connection with his biological father, Stallone’s younger sibling, actor/musician Frank Stallone, joined Sly in talking candidly about their father’s apparently unending meanness—which, over the brothers’ maturity, changed from verbal and physical assault to jealously, destroying, indifference, and nastiness. The anguish of seeing his kids do better than him, something that would be any parent’s dream come true, appeared to be the driving force behind everything.

Sly’s mom, boxing organizer Jackie Stallone, relocated with Sly’s younger brother to Philadelphia, the location for most of the “Rocky” films, and it was there that Sly learnt about polo with his biological father. The scene when the brothers are separated from one another is so emotionally charged that it might have been expanded into its own film. The most moving parts of the film are those in which Stallone describes the difficulties he had communicating with his father, often using dry, restrained phrasing that only serves to emphasize how terrible things must have seemed for him.

In other respects, “Sly” is a disappointingly incomplete work, one that teeters on the brink of genuine understanding but never quite crosses over. It was wise of Zimny to place Stallone in the spotlight and let him take the viewers through his life using the same pleasant, articulate, man-of-the-people enthusiasm that he delivered to so many television performances over the years. However, it seems that the film softens both Stallone or his films in order to appeal to a wider audience.

The fact that traditional Hollywood because the snarkier portions of media used Stallone as a joke for being an unrefined palooka wounded him, and it seems much more unjust today than it would then. The film “Sly” only briefly touches on the fact that Sly was an Italian-American from New York with difficulty speaking who became prominent and wealthy without first learning the way to be smooth and classy, allowing Stallone along with other interviewees to refer to him as an outsider or underdog.

Stallone’s marriages with the exception of the third, which is only touched upon briefly and children are not discussed at length, with the tragic exception of his 36-year-old son, Sage. (When Stallone admits he should have prioritized his family above his career, it’s an emotionally powerful moment, and it makes you wish the movie had dug more into the subject.)

Unfortunately, “Sly” isn’t quite as in-depth as the piece itself. The first half is devoted to setting up the original “Rocky,” while the second half is a brisk dash through the remainder, with breaks for favorites like the “Rambo” movies and “Copland.” It also glosses over some of the broader significance of Stallone’s career in the United States over the twentieth century. For certain ideologies, he exemplified the ideal.

While the first film in the “Rambo” series featured a devastated the country vet as the protagonist and hippie-hating forest law enforcement and National Guardsmen as the antagonists, the second film in the series, released in 1985, was a P.O.W. rescue fantasy in which Rambo slaughtered bushels of Vietnamese and numerous of Russians. In the same year, Reagan supporters also welcomed the “Rocky” franchise with the release of “Rocky IV,” which paired the title character against a giant, grinning blonde Soviet who looked like she walked out of a James Bond film.

Over the course of the following 15 years, Stallone was essentially the polar opposite of Springsteen, embodying white ethnic resentment and conservative fury. An article on the cover of Newsweek in 1985 titled “Showing the Flag: Rocky, Rambo, and the Rebirth of the American Hero” proclaimed him to be the next John Wayne. It might have been interesting to have heard Stallone discuss the whole thing with his trademark wit and judgmental intelligence, but instead “Sly” avoids politics like Rocky does a haymaker.

I’d be willing to guess that New York Times cultural reporter Wesley Morris and screenwriter/director Quentin Tarantino had much to say on all of these themes irrespective of whether Zimny contacted them for their comments. Perhaps among the outtakes is a more difficult, edgy version of the film. When encouraged by interviewers, Stallone will go into contentious topics and provide fantastic quotes.

He had recently completed a full-length film about his creative process titled “The Making of Rocky vs. Drago,” which centered on his delayed re-cut of “Rocky IV,” where he reinstated a lot of character growth that he had abandoned to shorten the picture’s operating time in 1985. The actor was in his mid-seventies if “Sly” was filmed. The movie is going to be more fulfilling for followers of Stallone as an artist and symbol, since it gets more thoroughly into the nuts-and-bolts of cinematography, image-shaping, but mental health, and delivers as much personal knowledge. Even while this is clearly Stallone’s film, he seems less reserved and less like he’s trying to push his own personal brand.